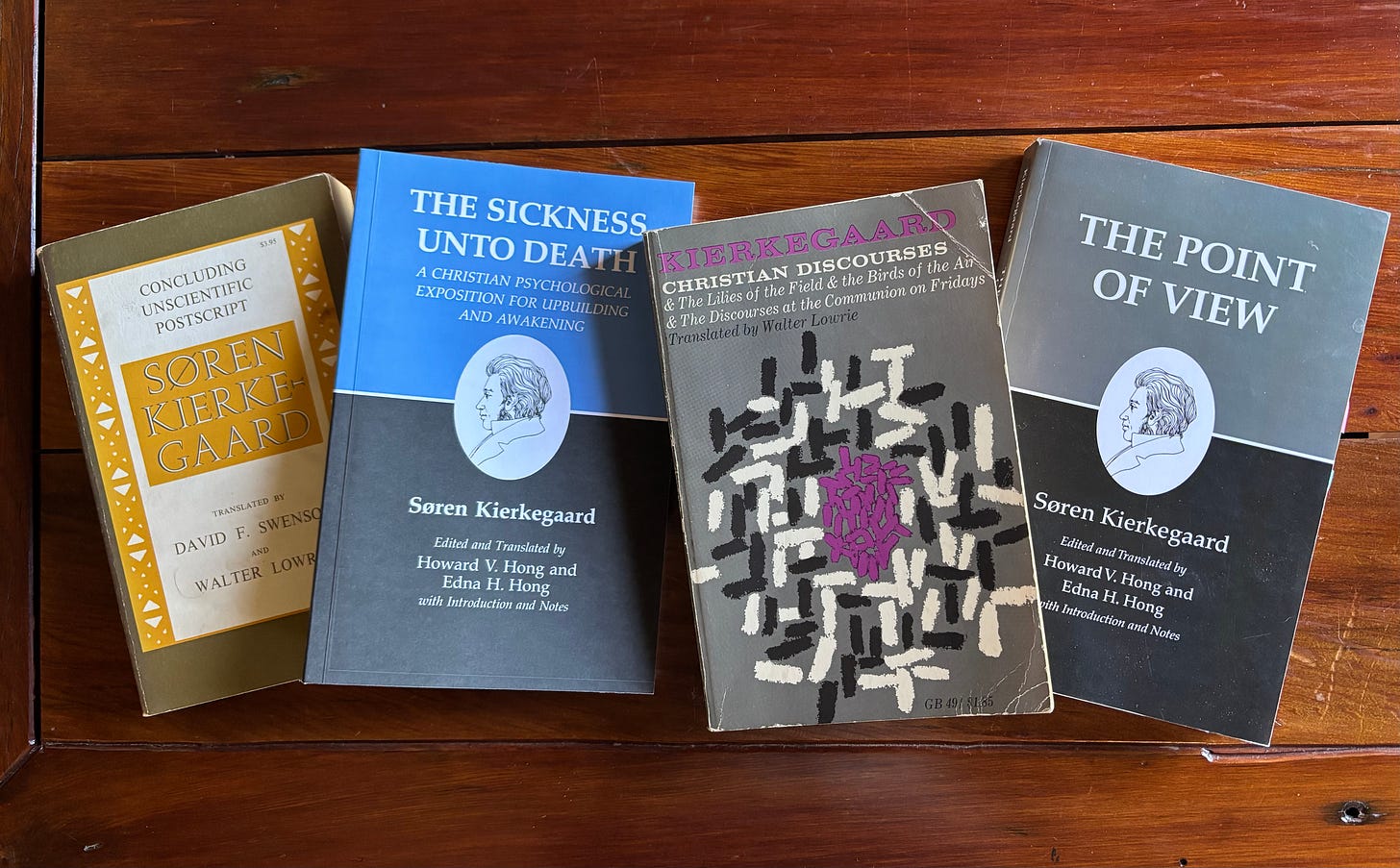

Different Translations, Different Kierkegaards

Having different translations side by side will illuminate Kierkegaard better for you

As I develop my MPhil thesis on Søren Kierkegaard’s theology of prayer into a publishable manuscript, I’m going through the rigorous process of what shall stay and what shall go. I want to reproduce this section of my thesis as a Substack post, in case it is of interest or use to others. I focus on the two main groups of translators of Kierkegaard here; for those looking for a more detailed list of all English translators of Kierkegaard, I’ve compiled an (imperfect) list (see list #7). The text here has been edited and reshaped a little, so that it might read comfortably and as a stand-alone piece.

I am indebted to Kierkegaard scholars C. Stephen Evans and M. G. Piety for much of this section.

~~~

Howard and Edna Hong’s translations of Kierkegaard, published by Princeton University Press, remain the customary and standard resources for contemporary Kierkegaardian scholarship to cite from. There are a number of reasons for this, one of which is the Hongs’ reputation as precise translators who were driven by an attention to word-for-word accuracy in Kierkegaard’s Danish. Their approach was motivated in part by a desire to provide a consistent philosophical vocabulary for Kierkegaard. Yet, Kierkegaard’s love of the Danish language and his talent as a poet and master of genre make him resistant to a too-regimented treatment in translation.1 Unfortunately, the motivation to provide a precise and internal philosophical vocabulary for Kierkegaard has gone on to have a direct effect on both scholarly and lay interpretations of Kierkegaard. For example, the Hongs often lack a sensitivity to Kierkegaard’s subtle Scriptural allusions, and fail to reproduce them in translation, something that is often preserved in Walter Lowrie’s and husband-wife team David and Lillian Swenson’s translations.2 This has, in turn, obfuscated just how saturated Kierkegaard was in Scripture, and just how much it inspired and shaped his thinking and philosophy. The subject of prayer has also been inadvertently obscured in the Hongs’ translations of Kierkegaard’s writing, which I will illuminate here with just two examples.

In the opening pages of Kierkegaard’s 1845 discourse On the Occasion of a Confession, the Hongs translate the following:

“To be sure, a poet has rightly said that a sigh to God without words is the best worship [Tilbedelse]; then one could also believe that the infrequent visit to the sacred place, when one comes from far away, would be the best worship, because both contribute to the illusion.”3

Swensons’ translation, however, reads differently:

“A poet has indeed said that a sigh without words ascending Godward, is the best prayer [Tilbedelse], and so one might also believe that the rarest of visits to the sacred place, when one comes from afar, is the best worship, because both help to create an illusion.”4

There is a different choice of word here; the Hongs translate Tilbedelse as “worship” whereas Swenson translates it as “prayer.”5 According to Ferrall-Repp’s 1845 Danish-English dictionary, the word Tilbede carries two meanings: first, “to adore, worship” and second, “to obtain, procure by prayer.”6 It appears at first, then, that the Hongs provide the most accurate translation, as “worship” is listed as the first and primary definition. However, identifying the poet Kierkegaard is referring as Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and considering the broader context of both Kierkegaard’s purpose and Lessing’s point challenges this word choice.

Kierkegaard remarks in his journal:

“If I remember correctly it is in [the play] Minna von Barnhelm that Lessing has one of the characters say that a sigh without words is the best way to pray to God. That sounds fine but actually means that one does not really dare or does not want to get involved with the religious but merely wants now and then to gaze out upon it as upon the boundaries of existence...”7

Though it is true the first definition of Tilbede listed by Ferrall-Repp is “to worship,” given Kierkegaard’s reference to Lessing’s play and his criticism of Lessing’s sentiment that sighing is a type of prayer, it is clear that Tilbede should be rendered as “prayer” in the English text. Though the Hongs are more accurate with regards to the word’s literal meaning, Swensons’ is more accurate to Kierkegaard’s meaning. In reading Swensons’ translation of this passage, then, one gains insight into Kierkegaard’s thought on prayer, whereas the reader of the Hongs’ misses out and does not.

The next example comes from Kierkegaard’s prayer discourse One Who Prays Aright Struggles in Prayer and Is Victorious—In That God is Victorious. Though this section of text is lengthy, both versions of this one sentence are presented in full for the sake of comparison, with the more notable differences being bold type-faced. This not only highlights the differences in word choice or phrase, but also shows a couple of interpretive differences that present competing meanings to Kierkegaard’s original. The reading experience is also notably different.

The Hongs’ translation reads:

If someone objects that then one might just as well be silent if there is no probability of winning others, he thereby has merely shown that although his life very likely thrived and prospered in probability and every one of his undertakings in the service of probability went forward, he has never really ventured and consequently has never had or given himself the opportunity to consider that probability is an illusion, but to venture the truth is what gives human life and the human situation pith and meaning, to venture is the fountainhead of inspiration, whereas probability is the sworn enemy of enthusiasm, the mirage whereby the sensate person drags out time and keeps the eternal away, whereby he cheats God, himself, and his generation: cheats God of the honor, himself of liberating annihilation, and his generation of the equality of conditions.8

Swensons’ reads:

If someone were to object that then one might as well keep silent, since there is no probability of winning others, then he only proves that while his own life has supposedly thrived and flourished in probabilities, so that every enterprise of his in the service of the probable has had success, he has never dared to venture, and so has never had or given himself opportunity to consider that probability is an illusion, while to venture is the truth which gives human life and human relations content and meaning. To venture is the well-spring of enthusiasm, while probability is its sworn enemy, the illusion with which the worldly man fills out the time and keeps the eternal at a distance, by which he defrauds God and himself and the race: God of the honor, himself of the salvation that lies in annihilation, and the race of the equality of the conditions.9

Between these two translations Swensons’ renders “the worldly man” while the Hongs’ render “the sensate person,” and Swensons’ provides “the salvation that lies in annihilation” while the Hongs’ provide “liberating annihilation.” It is notable that the translation choices of salvation and worldliness carry theological connotations, while liberation and sensation carry a broader, more neutral meaning—which is truer to Kierkegaard’s meaning in this case is a separate matter, but these sublties of difference are nevertheless important to highlight, as the reader’s experience is influenced either way.

Of greatest note is the difference between Swensons’ “to venture is the truth” and the Hongs’ “to venture the truth is.” Here there is a clear difference of meaning: either Kierkegaard means that the very act of venturing is to be in accordance with the truth, or he means that one must venture correctly and in line with the truth in order to accord with the truth. In the wider context of the discourse, Swensons’ translation is more appropriate, as it is by the very act of struggling in prayer that the individual realizes her own victory through God’s victory. It is not, in other words, by praying in just the right way that the ontological reality of God’s victory for the individual comes to bear upon her.10 Similarly, “supposedly” thriving (Swensons’ rendering) is quite different to “very likely” thriving (the Hongs’ rendering). To say that one has very likely thrived is to give more credence to that individual’s actually thriving, rather than the more appropriate “supposedly” thriving, which insinuates an individual may think she is thriving when in fact she is not.

The overall point of Kierkegaard’s thought in this passage is that an individual proves she has never genuinely striven beyond thinking in probabilities when she endorses keeping silent before others instead of persuading them to struggle in prayer.11 The individual living in probabilities concludes that it is futile to try to persuade others that prayer has benefit and appeal, while the individual with experience in prayer knows she can be hopeful to the contrary despite it being the case that mere words are not enough to turn another person into a strive-er in prayer. Swensons’ translation gets you to this understanding, while the Hongs’ translation makes it a little more difficult, and a little less obvious.

One case in point: Kierkegaard was one of the first people to defend his dissertation (On the Concept of Irony) in his native Danish, writing a special petition to the King in order to gain the permission to do so. Traditionally, the hours-long defense was given in Latin (of which Kierkegaard was also notably well spoken in).

The Hongs do sometimes indicate the Scriptural allusions with footnotes, but this is paltry fare for the person who wishes to read those allusions from within the text. The Hongs also frequently fail to make note of these allusions, perhaps in order to spare the reader from being overwhelmed and inundated by footnotes, or perhaps because they did not see them.

Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions (TDIO), trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993, p. 16-17. Bold typeface added.

Swenson, Thoughts on Crucial Situations in Human Life, p. 10. Bold typeface added.

The two Danish words for prayer are Bøn (a noun) and bede (an adjective). Having no formal instruction in Danish myself, it is interesting to note that Tilbede contains bede, which suggests bede functions like a root word in Danish. Ferrall- Repp’s Danish-English dictionary does not contain the word Tilbedelse, which appears to break down like this: Til—bede—lse. (bede means “to beg, ask, desire, crave, beseech, entreat, supplicate; to pray, say one’s prayers,” according to Ferrall- Repp p. 24).

Ferrall-Repp p. 327. A special thanks goes to M.G. Piety for the information she has made available on her blog Piety on Kierkegaard. It was on her blog that I learned about, and found access to, Ferrall-Repp’s Danish-English dictionary.

JP IV 4364 / Pap VI A 2. (Søren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Papers, trans. by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong, Bloomington and London: Indiana University Press 1967–1978).

The line in the play reads “One thankful thought to Heaven is the best of prayers!” TDIO p. 159.

Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses (EUD) trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992, p. 382.

Edifying Discourses: Volume IV, trans. David and Lillian Swenson, Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1943-1946, p. 119-120.

Admittedly there is a tension here. Kierkegaard consistently holds the powerlessness of the individual before God in tension with the necessity of consistent action on the individual’s part in order to experience the transformation of becoming human. Kierkegaard has much to say on what praying well looks like too—simply because one prays, it does not mean that the individual is praying at her best or is not in some way in need of learning or instruction. Kierkegaard expands on this in places such as “Watch Your Step in the Lord’s House” (on Ecclesiastes 5:1, see CD p. 163-175) and “The Tax Collector: Luke 18:13” (see WA p. 127-134). Nevertheless, in the present case Swensons’ translation does better by implying it is God and his victory that animates and enables the praying individual.

Earlier in the discourse Kierkegaard made much of the point that one who has experience in persevering and struggling in prayer cannot convey in words why striving in prayer is worth it.

Have you seen the Provocations paraphrase of Kierkegaard? Very readable, it’s online free as a PDF.