“The Only Proof of a Conviction is One’s Life”: Fredrika Bremer on Søren Kierkegaard, and Søren Kierkegaard on Fredrika Bremer

This is the promised follow-up piece, long overdue, to my first Substack posting “Proof of Kierkegaard in 19th century America.” This has been a fun, but much more involved piece than I had originally anticipated. The piece itself will likely show why…

I wish to offer thanks to my local public library and Gustavus Adolphus College, whose efforts through InterLibrary Loans brought to hand what are otherwise difficult resources to get ahold of (being obscure and expensive). I remain so tickled, as my grandmother would say, that two private Midwestern colleges would be willing to send their books all the way to a small public library in semi-rural California (my apologies, for not noting down the name of the second college before it was too late). Thanks also to the Zip Books program funded by the California State Library. I am grateful as well for Internet Archive and Google Books, who by now we’ve all used in both our serious and for-fun internet ramblings. Through them I’ve been able to access primary and secondary texts that would have been very difficult, if not impossible, to track down.

In May 1849, well known and well regarded Swedish novelist Fredrika Bremer sent a note of introduction to Søren Kierkegaard’s place of residence. She wished to meet this curious figure, whom she has heard much about in her conversations with ‘the good people of Denmark’ during her six month visit to Copenhagen. After a period of silence and a follow up note, Bremer received a written denial for an interview. Perturbed but not dissuaded, Bremer went on to put Kierkegaard in the travel book she was writing on Denmark anyway, mentioning him with two others as one of Denmark’s key philosophers…and much to Kierkegaard’s annoyance, when he encountered what Bremer said about him.

This brief exchange between Bremer and Kierkegaard would be historically ancillary, if it were not for the significance of Bremer’s influence on her contemporaries, and for Kierkegaard’s alarming accusations made against her character in his private journals. Their written impressions of one another carry implications that bear upon how Kierkegaard was received and interpreted by English readers in the mid to late 19th century. They also contribute further evidence to account for in the complicated question of Kierkegaard’s view of women. Though Kierkegaard’s opinion of Bremer is largely affected by his feelings towards his nemesis Hans Lassen Martensen, of whom Bremer espoused great admiration, Kierkegaard also levies judgements against Bremer that are impossible to prove, but also important to account for.

In what follows, I will present Bremer and Kierkegard’s brief letter exchange during the former’s visit to Copenhagen. After presenting some thoughts and speculation on their exchange, I will then present in loose chronological order Bremer’s public and Kierkegaard’s private thoughts on the other person. Normally it would be best to summarize most of this primary material and present to the reader key excerpts, all for the sake of brevity and readability. Circumstances feel unique enough, however, to warrant the presentation of Bremer’s and Kierkegaard’s writing in full—in this way all of the primary material is in one place, and at the disposal of the reader. Following the overview of Bremer’s and Kierkegaard’s written comments on the other, I will conclude with some analysis and speculation on their relationship. Watching the unfolding of Fredrika Bremer on Søren Kierkegaard and Søren Kierkegaard on Fredrika Bremer demonstrates just how difficult it can be to truly see and understand another well.

I. The Exchange of Letters

Towards the end of her stay in Copenhagen, Fredrika Bremer sent a playful note of introduction to Kierkegaard, asking him to pay her a visit. She addresses the letter to one of Kierkegaard’s cast of pseudonyms, Victor Eremita, and describes her wish to discuss his book Stages on Life’s Way.

To Victor Eremita:

A recluse, like you (even though she lives in the midst of society), sincerely wishes to meet you before she leaves this country—partly to thank you for the heavenly manna in your writings and partly to speak with you about Stages of Life, the metamorphoses of life, a subject that at present is more profoundly interesting than ever to her. She cannot call on you. You will easily understand why. Would you be willing to call on her? I know it is a lot to ask. But the excellent men of Denmark have made me reckless. They have given me grounds to believe that one cannot desire too much of them nor hope for more than they can give.—I shall be at home on Thursday, Ascension Day, after church and again in the afternoon from 4 p.m. until evening if I may hope to expect you. If I may do so, if you would come for a while, how kind you would be to the most sincerely gratefulFrederika Bremer1

Kierkegaard apparently does not respond to Bremer, and after the passage of a few days (with no specific date on the letter), she sends a shorter follow-up note, this time directly addressed to Kierkegaard:

You will, I am sure, have the kindness to give my messenger a word as to whether I may expect you to call on Thursday or some other day, or, if you are not at home when this arrives, to send a message to my home!--

FR. B.

Tuesday evening.

Bachelor of Divinity Mr. Søren Kierkegaard.

Gammel Torv.2

This note elicits a response, of which we have a draft left in unpolished paragraphs and sentences:

It is my hope that I shall not be misunderstood, for it would grieve me deeply were I to be misunderstood, but even if that were so, I still cannot accept this invitation. Unaccustomed as I am to being understood, I am all the more accustomed to having to endure being misunderstood. The sole difference consists in this, that sometimes it is easy for me to endure being misunderstood, and sometimes I find it a heavy burden—as I would in this case, if I were misunderstood.

[Deleted: Permit me a straightforward and forthright word: I really feel it to be a punishment for my singular way of life that through my fault a lady is brought so unjustly into an awkward situation.]

From Sweden's authoress, famous throughout Europe, as though I did not know how to value and appreciate such a distinguished lady's benevolent attention.

Just one more word: you refer to your invitation almost as if it had been ventured recklessly. Indeed that is almost to mock me. No, I am better versed with respect to recklessness—and I appeal most recklessly to your own judgment. I venture the utmost in recklessness, I who decline the invitation, I the unworthy; I venture to ask you to accept, as completely and fully as it is intended, my most sincere thanks for the invitation. Indeed, I venture the very utmost in recklessness, I venture to believe that you will do so, as I now most sincerely beg you to do; and this I do—I who will not come, I remain sincerely in a debt of gratitude.

[In margin: And yet, yet this is after all not so reckless, because I do have some idea of your exalted character.—]3

~Why does Kierkegaard ignore Bremer’s first note? Why does Kierkegaard decline Bremer’s request for a visit? More can be surmised about this after reading their later reflections on each other, but at present a few things can be noted directly from the letters. Primarily, that Bremer speaks of being unable to call on Kierkegaard herself, that she chooses Victor Eremita to address Kierkegaard, and that Stages on Life’s Way is her book of choice for discussion.

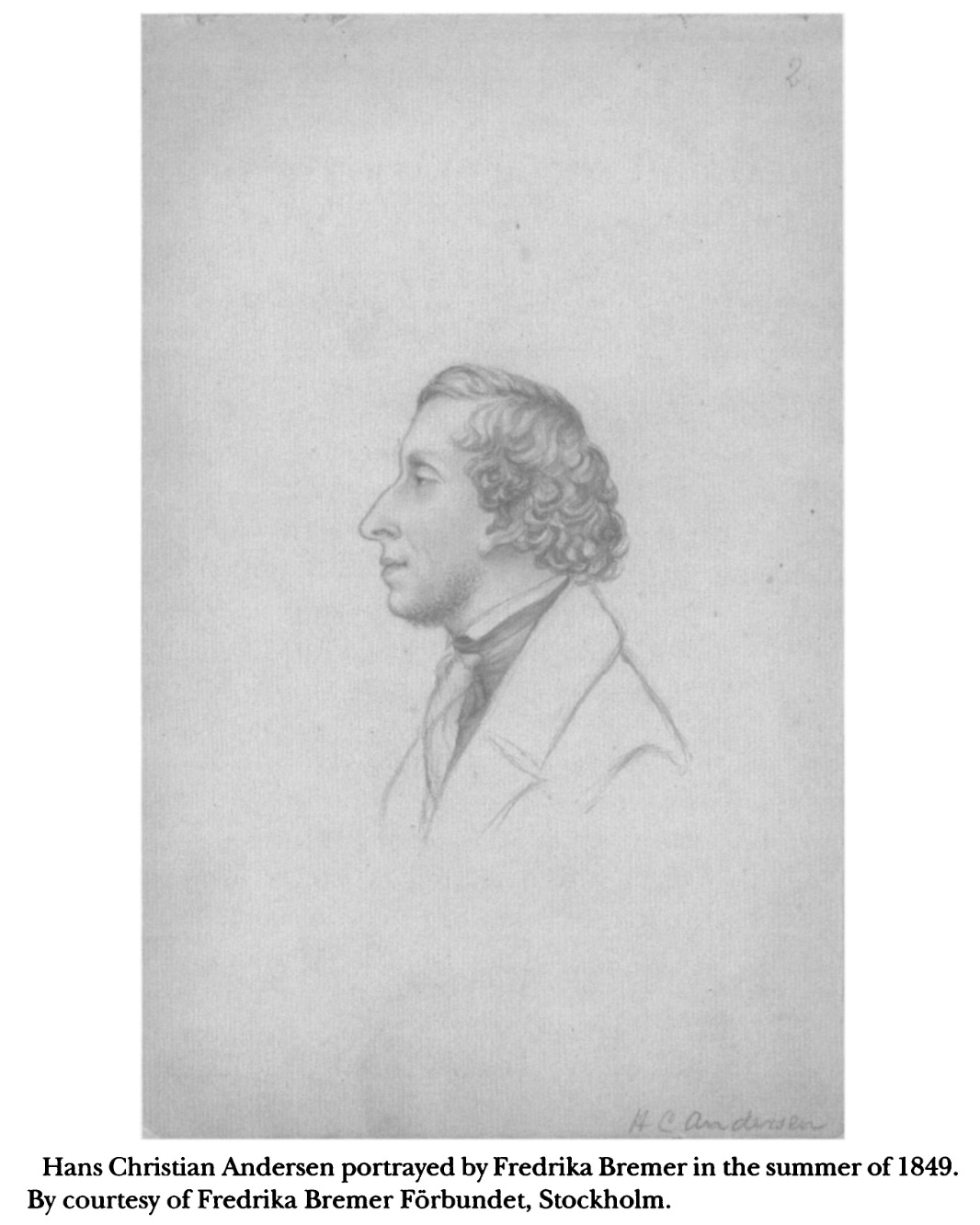

It is a little peculiar that Bremer cannot call on Kierkegaard herself. At this time Bremer was growing ever more into an outspoken proponent of women’s emancipation, which began through a demonstration of her actions—she made her own travel plans, did not travel with a chaperone, and was unashamedly yet politely willing to introduce herself to new acquaintances. She was not shy about visiting other gentlemen in Copenhagen, including unmarried men like Hans Christian Andersen. Decorum could therefore not have been the reason for Bremer’s calling on Kierkegaard. Private or domestic reasons are equally out of the question too, as Bremer writes that Kierkegaard will “easily understand why” she cannot call. It is possible that Bremer is being playful, knowing she is addressing a pseudonym (Victor Eremita), who is of course impossible to meet with in a literal sense. Alternatively Bremer could be attempting delicacy, not for her sake, but for Kierkegaard’s, given her joint identification with him as being a “recluse,” and given recluses don’t appreciate unknown callers. Neither of these possibilities are entirely satisfactory, though, which leave Bremer’s motives for asking Kierkegaard to call on her a mystery.

Certain aspects of Bremer’s note very likely acted as irritants for Kierkegaard, too, which would have furnished reasons to deny a visit. Primarily, there is Bremer’s choice to address Kierkegaard with his pseudonym Victor Eremita in relation to the book Stages on Life’s Way.

Victor Eremita plays a small role amidst a cast of other characters in the beginning section of Stages on Life’s Way, yet given the wide array of pseudonyms that feature in Stages, others offer a more natural a choice.4 There is Judge William, for example, who writes all of the second part of Stages and focuses on the institution of marriage—a subject matter enmeshed with the subject of women’s rights. Judge William even names emancipation within his defense of marriage, stating his open disregard for it: “I was brought up in the Christian religion, and although I can scarcely sanction all the improper attempts to gain the emancipation of woman, all paganlike reminiscences also seem foolish to me” (SLW 124). Bremer could also have chosen Hilarius Bookbinder to address Kierkegaard, as he was the pseudonymous publisher of Stages.

Victor Eremita, on the other hand, is most obviously associated with Kierkegaard’s first book Either/Or—one of Kierkegaard’s best-selling books, and the only one to receive a second printing during his lifetime. This second printing was released about when Bremer wrote her letter of introduction, so it is possible Bremer chose Victor Eremita because he was a more popularly known pseudonym. It could also be because “Eremita” means “hermit” in Latin, which would be on theme with Bremer’s association of Kierkegaard as a recluse. It is worth noting, though, that whether Bremer knew it or not, singling out Stages on Life’s Way for private discussion could have all too easily signaled an interest in subjects other than philosophy to Kierkegaard.

Stages had not been a popular book in it’s own right, and was most famous to Copenhageners as the cause of a public scandal between Kierkegaard and a popular satirical newspaper called The Corsair. What scholars now call “the Corsair affair” began with a careless and flippant review Peder Ludvig Møller wrote of Stages in December 1845. Møller went as far as to breech the unspoken etiquette of respecting an author’s pseudonymity and keeping literary reviews impersonal, which saw Kierkegaard respond to Møller with increasing bite through his pseudonym Frater Taciturnus (another of the more main pseudonyms of Stages on Life’s Way). After a little back and forth Kierkegaard dropped the matter, but from then on The Corsair would use Kierkegaard as a comical figure, a tease that climaxed with nine issues of The Corsair containing 1-3 satirical bits a piece on him between January 9, 1846 to January 7, 1848.5

It seems impossible that Bremer, having immersed herself in the social circles of Copenhagen all winter and spring, and inquiring into the intellectual life of Denmark…it seems impossible that she would have heard nothing of Kierkegaard’s war of words with The Corsair. However, it is equally unlikely that Bremer would have chosen Stages for the express purpose of reminding Kierkegaard of an unpleasant scandal. It seems Bremer merely wanted to interview Kierkegaard about Stages rather than read it, a wish that is innocent enough. Yet, for an author like Kierkegaard, an unwillingness to deeply engage with the material reveals a mark of disingenuous interest in its contents, and an insincere commitment to one’s own inner transformation into being both a human being and a Christian.

Already, then, stark differences divide these two thinkers, with the clash showing through their very brief correspondence—an interview is requested twice, and denied. It is rather the writing that exists after the fact which greatly illuminates these letters. Bremer wanted more than to discuss Kierkegaard’s thoughts for herself—she wished to assess him as one of Copenhagen’s noted philosophers of the day. Failing to secure an interview, Bremer continued in her purpose and included an assessment of Kierkegaard in her travelogue anyway…

II. Bremer on Kierkegaard: Liv i Norden

Bremer’s travelogue, entitled Liv i Norden (Life in the North) was published in Denmark and Sweden soon after she left for London (and then the United States).6 Its purpose was to give an overarching sense of the culture and ways of modern Danish life to her international readership, but was perhaps even more so to be both an act and model of women’s emancipation.7 Bremer’s comments on intellectual modern life in Copenhagen are sandwiched between protracted praise of the social efforts of women, and subtle nudges of encouragement on Denmark’s movements towards the emancipation of their own “subjected classes.”

Liv i Norden begins with praise of the recent developments Danish women were making with underprivileged children, and then begins patterned reflections on Copenhagen’s intellectuals. These often start with laudatory descriptions of the field in question before going on to list a few leading figures in each category.8 Bremer starts with Copenhagen’s theater life, and then proceeds to consider church life, the poets playwrights and “literati” of Copenhagen, painters and musicians, naturalists and scientists, and then ends this style of analysis with Denmark’s philosophers. Bremer then concludes her short book by explicitly considering Denmark’s movements towards emancipation. “We look up on the great rising middle–class, which daily grows in the North, by additions from the aristocratic order, as well as from the artisan-classes, who make labor their honor, and the noblest humanity the object of their education. We behold an emancipation in the best sense of the word, which elevates more and more the subjected classes, and levels the separating barriers of rank and fashion.”9

Bremer’s analysis of Copenhagen’s philosophers begins with remarks on one of Kierkegaard’s old philosophy teachers at the University of Copenhagen, Frederick Charles Sibbern (1785-1872). Sibbern receives the lengthiest attention from Bremer before she turns to Hans Lassen Martensen with praise and then, lastly, to Kierkegaard:

While Martensen, with his wealth of genius, casts from his central position light upon every sphere of existence, upon all the phenomena of life, Søren Kierkegaard stands like another Simon Stylites upon his solitary column, with his eye unchangeably fixed upon one point. Upon this he places his microscope and examines its minutest atoms, scrutinizes its most fleeing movements, its innermost changes; upon this he lectures; upon this he writes again and again, infinite volumes. Everything exists for him in this one point—the human heart; and as he ever reflects this changing heart in the eternal, unchangeable, in Him “who became flesh and dwelt among us,” and as, amidst his wearisome, logical wanderings, he often says divine things, he has found in the gay, vivacious Copenhagen not a mean public, and principally of ladies. The philosophy of the heart must be interesting to them. About the philosopher who writes on this subject, people say good and bad, and—wonderful things. Solitary lives he who wrote for “That Individual,” inaccessible, and in fact known to none. During the day he may be seen passing up and down in the throng of the most crowded streets of Copenhagen; by night, lights are seen to shine from his solitary house. Rich, but regardless of wealth, he appears to be rather of a jaundiced and irritable temper which finds occasion of displeasure even against the sun if it shine otherwise than he wishes. For the rest, in him is seen something of that metamorphosis of which he likes to write, which he has experienced in himself, and which has led him from a skeptical waverer, through “sorrow and trembling,” to the hill of light, whence he now talks with inexhaustible power of “the Gospel of Suffering,” of “deeds of love,” and the “inner mysteries of life.” Sören Kierkegaard belongs to those few profoundly introverted characters which have been met with from the most ancient times in the North, though oftener in Sweden than in Denmark, and it is to his kindred spirits that he talks about the sphinx in the human breast; that silent enigmatical, above all, mighty heart.10

Since all available evidence indicates that Bremer never met or interviewed Kierkegaard, we know that she bases these judgements of him off reports and second hand news (admitting as much herself, that ‘people say good and bad’ of Kierkegaard). Unfortunately, in doing so, Bremer played a hand in perpetuating myths about Kierkegaard, which include considering Kierkegaard as a solitary reclusive, as a temperamental and poorly natured person, and as an obsessive who misses the larger picture in his critique of modern thought. Little of the estimations of Kierkegaard’s friends appear in Bremer’s report.

In a letter following Kierkegaard’s death, we have evidence that it was Hans Christian Andersen who first called Kierkegaard a Simon Stylites.11 Jibes from The Corsair are present in Bremer’s assessment too, such as Kierkegaard’s supposed ill and reactionary temper when the sun does not shine (since The Corsair was widely read, Bremer did not need to read or know of The Corsair’s existence in order to be exposed to its sentiments through others). One Corsair bit likened Kierkegaard to a comet, teasing his appearance and self-importance, and calling him an eccentric. Another names the sun as revolving around Kierkegaard rather than Kierkegaard revolving around the sun, attributing to Kierkegaard volatile emotions. Still another makes a satire of the church calendar, elevating Kierkegaard and his pseudonyms to days of the week, marking the setting of the sun followed by a day of prayer.12 An additional hint of Møller and The Corsair is present when Bremer writes that Kierkegaard wrote autobiographically of his own experiences in Stages, saying “in [Kierkegaard] is seen something of that metamorphosis of which he likes to write, which he has experienced in himself…”.

The opinions of Kierkegaard’s nemesis Hans Lassen Martensen are also detectable in Bremer’s assessment, which we will soon see Kierkegaard claims himself. It is likely owing to Martensen that Bremer writes Kierkegaard is “unchangeably fixed upon one point,” reducing her own earlier interest in his “metamorphoses of life” into a single “metamorphosis.” Rather than Kierkegaard’s writing on a wide array of subjects spanning suffering, love, and the “inner mysteries of life,” Kierkegaard is instead a singular ‘philosopher of the heart’ who consequently will be of singular interest to ladies.13 This is all the more interesting when it is considered that earlier in Liv i Norden Bremer observes “the Dane does not willingly talk of his heart…[the Copenhagener] has frequently head at the expense of heart…”. It is a backhanded compliment to Kierkegaard, then, that in Bremer’s estimation he does not fit inside the norm of a typical Copenhagener. Perhaps this is why Kierkegaard stands out to Bremer as more than a mere oddity, and why he sometimes says “divine” and “wonderful” things. Nevertheless, Bremer’s joining the opinion of others that Kierkegaard’s philosophy stands outside of the all-important ‘philosophy of life’ could not have been farther from what reception history has gone on to show. Kierkegaard is remembered today as a philosopher of life who continues to widely influence philosophers and the thinking public, while Sibbern and Martensen are only remembered by a niche of scholars.

III. Kierkegaard on Bremer: Response to Liv i Norden

In total there are 6 mentions of Fredrika Bremer in Kierkegaard’s journals.14 As stated earlier, I would normally keep the bulk quotations to a minimum, but here I want to present as much of the primary material as possible, as it is difficult and time-consuming to locate these entries on one’s own. It’s also important to let Kierkegaard speak for himself, while dignifying to read primary material on one’s own. On the lengthier entries where Bremer is mentioned amidst a wider conversation I have shortened them to help keep the focus on Bremer or matters relating to Bremer. I have highlighted her name in bold for easy locating, and have presented the entries in order of relevance to the discussion here, rather than attempted to place them chronologically.

Kierkegaard’s first mention of Bremer in his journals is the longest description of her character that we get, and also the most accusatory:

Naturally one seeks the society and company of everyone who amounts to anything, everyone who concerns himself with pronouncing judgment on literary matters and the like. One also keeps a careful eye on foreigners. It helps, you see.

It has now pleased Fr. Bremer to bless Denmark with her judgment. Naturally it consists of echoes of what the people concerned have said to her. This can best be seen in the case of Martensen, who has had quite a lot to do with her. She was kind enough to send me a courteous note inviting me to have a conversation with her. Now I almost regret that I did not reply as I had originally thought of doing, with merely these words: “No, many thanks, I do not dance.” But in any case I declined her invitation and did not go. So I get to hear in print that I am “inaccessible.” It is probably owing to Martensen’s influence that Frederikke has made me into a psychologist and nothing else, and has provided me with a significant audience of ladies. It is really ridiculous―how in all the world I can be considered a ladies’ author[?] But it is owing to Martensen. He has surely noticed that his star is in decline at the university. It will certainly be droll for R. Nielsen and those who are truly of the younger generation to read that I am a ladies’ author.

[in the margin] She lived here for quite a while and had physical intercourse with famous people. She wanted to have physical intercourse with me, but I was virtuous.15

According to Kierkegaard, Bremer is a dilettante and a quidnunc—she suspiciously seeks out the company of notable people, believes what she hears from them, and publicly passes judgement on matters that she is superficially familiar with. Kierkegaard takes it a step farther though, when he indites her for having physical intercourse with famous people and wishing to do so when she first wrote him.

Before we examine this accusation, though, or consider how Kierkegaard’s claim of Bremer’s sexual promiscuity reveals something of his own understanding of women, we must first pause and consider Kierkegaard’s relationship to his contemporary, Hans Lassen Martensen. Not a single journal entry exists on Bremer that does not also levy complaint against Martensen, and we cannot hope to fully understand Kierkegaard’s reaction to Bremer without first understanding something of Kierkegaard’s regard of Martensen.

To put it melodramatically, Hans Lassen Martensen was Kierkegaard’s archenemy.16 From early on they knew each other through the University of Copenhagen, and remained intellectual rivals up to and even passed Kierkegaard’s death in 1855. In earlier days Kierkegaard seems to have held a respect of Martensen’s intellect and an interest in his person, having Martensen personally tutor him in philosophy in 1834, and frequently visiting Martensen’s mother to ask after him when he was away on an extended journey.17 Five years Kierkegaard’s senior, Martensen began as a philosophical-theology lecturer at the University of Copenhagen in 1837 at just age 29, with Kierkegaard in attendance. “He was immediately able to captivate the imagination of the young students with his lecture style and his rich knowledge of the current situation of philosophy and theology in Germany and Prussia...[he] created a great sensation among both the students and the professors at the university.”18 Martensen was also part of Kierkegaard’s dissertation committee, and heard Kierkegaard defend his thesis On the Concept of Irony.19

When and why the relationship between these two young men began to sour is not easily identified. Martensen never showed sincere interest in Kierkegaard outside of someone who might be amenable to his own ideas, while Kierkegaard’s disagreements with Martensen appeared early on, but only gave way to personal dislike later into both men’s careers. Of all that we have available to us in print, little Martensen says of Kierkegaard is kind or complimentary. It seems almost reluctant on his part to recognize in Kierkegaard any real talent or insight, yet Martensen grants both more than once, even going so far as to extensively engage with Kierkegaard’s thought in his 1878 Christian Ethics…twenty-three years after Kierkegaard had died.20 On Kierkegaard’s part, Martensen’s trajectory as a professional was a key reason for his disdain, as Martensen’s popularity and success as a professor and later as a churchman strongly conflicted with Kierkegaard’s own views about how someone with power and authority in the name of Christ ought to act.21 That Martensen was too amenable to Hegelian thought was a crucial point of difference between them as well. While Martensen saw the practice and study of systematic theology as a central and even core part to the Church’s work and life, Kierkegaard saw the modern practice of systematics as being a category mistake, a mistaken identity of what a true relationship with God looks like. Kierkegaard kept his disagreements with Martensen veiled to the public eye for most of his life, writing instead copious criticisms in his private journals or disagreeing with Martensen’s philosophy without naming him in his published writings. Kierkegaard’s public criticism of Martensen came at the very end of his life, when Kierkegaard chose to openly attack the institution of the Danish Lutheran Church. It could be said that Kierkegaard’s protracted efforts against Martensen was his own uncompromising Nein!22

When Fredrika Bremer visited Copenhagen between the years 1848 and 1849, Martensen was close to finishing what came to be one of his most famous works: Christian Dogmatics: A Compendium of the Doctrines of Christianity. Bremer received an advance look at what Martensen had written during some of her visits to him, and then recorded a glowing forecast of what the public had to look forward to in Liv i Norden:

H. Martensen is, in the highest sense, a man of truth; he is still young, and in the prime of his powers, and through his living words, as well as by his philosophical writings, which are prized as highly in Sweden as in Denmark, he scatters abroad the seed of a new development of the religious life, both in the church and in science, and this through a more profound understanding of its being, thought the explication of the life of faith by the life of reason, through the union of deep feeling with a logical intellect. In his Systematic Exposition of Christian Doctrine, which it is expected will soon be printed, a full statement of his views is looked for. By what is known of these views from the works he has already published, it is hoped that they will lead to a new birth in the life of the church, in great and in small, in the state and in the solitary heart. The extraordinary clearness and distinctness with which this richly gifted mind can set forth in words the most profoundly speculative philosophy, his interesting and genial mode of exposition, make him a popular writer. In his forthcoming volume, we expect to find a work not alone for the learned. It is high time that Theology was made popular. Our Lord made himself so eighteen hundred years ago.23

Bremer’s praise does read as a little too much in unremitting esteem, and with Kierkegaard’s long established relationship of enmity with Martensen we can see how Bremer’s own words on Martensen would shape Kierkegaard’s judgement of her, just as much as her words about him would. Kierkegaard regarded Bremer as an impressionable and uncritical disciple of Martensen’s, which in some shape or form is reflected in his other journal entries about Bremer:

Frederikke Bremer will become popular in various circles because of this version of things. I live on here now, having voluntarily exposed myself to and continuing to endure the prolonged and yet perhaps the most bitter of martyrdoms, the martyrdom of ridicule (doubly painful because the context is so limited and because the measure of my endowments and achievements is generally recognized). With frightful mental and spiritual strenuousness I endure by continued writing in the face of constant financial sacrifices—and yet it is well known that I have not dropped one single comment on [this matter]. Frederikke's version is that I am so sickly and irritable that I can become bitter if the sun does not shine when I want it to. You smug spinster, you silly tramp, you have hit it! Various circles that are perhaps not so different will be united by this interpretation. On the one side Martensen, Paulli, Heiberg, etc., on the other, Goldschmidt, P. L. Møller [editors of The Corsair]. It was a wonderful old world—Martensen may witness "for God and his conscience"; did he not become Bishop and swathed in velvet and did not Frederikke run to him every day and read his Dogmatik, of which she got proof sheets (this is a well-known fact). And Goldschmidt may declare: It was a wonderful old world, I always had 3,000 subscribers. All of them together: it was a wonderful world; only Magister Kierkegaard was so sickly and irritable that he could get bitter if the sun did not shine when he wanted it to.24

Kierkegaard’s anger towards Bremer is owing to her joining in with others’ opinions of him, and also in her gaining additional favor amidst his adversaries by adopting their own opinions about him. Kierkegaard’s reading of Bremer’s comments in Life in the North closely coincided with his reading of Martensen’s fresh-off-the-press Dogmatics, detailed in his journal NB12, which only served to exacerbate his irritation towards them both. Kierkegaard thinks Martensen might have him in mind when the Dogmatics says “[the individual] cannot accomplish his sanctification by leading an egotistic, morbid, and isolated life,” and we can see a likeness in the sentiment with what Bremer reports of Kierkegaard.25

Kierkegaard was disappointed, though, that Martensen did not more openly and honestly engage with his own body of work in his Dogmatics, so Kierkegaard writes “A Reply” to Martensen in his journals. There Kierkegaard bemoans again how Bremer’s own praise and popularity lends further credence to Martensen’s work, as if assurances of how good Dogmatics is are necessary in order to convince people that the work is actually one of quality:

A Reply that I could be tempted to make:

Inasmuch as “the established order” is so strong that Prof. Martensen thinks that he can dismiss the entirety of my writings with two lines in a preface, it surely becomes my duty to take away the damping capacity of jest and the diverting capacity of indirection, which―in order to spare myself and others―I have employed until now in connection with my communications: to take these away and proceed in a direct manner. The established order is certainly strong enough; after all, it has Prof. Martensen, who, as can be seen from his preface, is considerably the stronger.

Thus, directly: the entire proclamation of Christianity as it is now heard really omits what is essential in Christianity. And, to make it entirely direct: Prof. Martensen’s work, in all its foolishness, is actually the betrayal and abolition of Christianity. Granted, this has helped him in his career and in the acquisition of worldly goods, but it is of course not identical with Christianity, which contains no § about providing worldly goods for Prof. M. by transposing Christianity’s message into unchristian forms of communication…it would be a great embarrassment if Prof. Martensen remained silent, for then people would say, Of course, it is indeed a purely worldly existence. But then he speaks―and provides assurances―and [the newspaper] Berlingske Tidende provides assurances that this is Martensen’s conviction, concerning which Miss Bremer and Flyveposten also provide assurances, and many believers who believe Martensen’s assurances assure us that one can quite safely believe them. Should not this be certain, seeing as there are so many assurances[?] And yet, it is suspect. For a life does not need one single assurance―it is of course something one can grasp. Where this is absent, the matter simply becomes more and more suspect the more assurances there are.26

It is not just that Bremer’s praise exacerbates the esteem of Martensen and the disregard of Kierkegaard in Copenhagen (which Kierkegaard ultimately attributes as reason for why he cannot leave Copenhagen and retire as a quiet country preacher—his public image is too destroyed by The Corsair, his opponents, and now ‘foreigners’ like Bremer, to leave without confirming all suspicion about him).27 What goads Kierkegaard further is that Bremer continued on to the United States with her reputation and opinions in tow. This complaint appears in a journal entry and two essay sketches in Kierkegaard’s papers:

For example, Martensen, the profound M., who has already found a connoisseur in the no less profound Frederikke Bremer, who profoundly prophesies that Martensen's Dogmatik will regenerate all scientific scholarship in the North, perhaps also in North America, where the forerunner, the traveling Fr. B. has now gone. Not only this, the no less profound [newspaper]—despite its superficial appearance—Berlingske Tidende, or wholesaler [Mendel Levin] Nathanson, who according to his own words (on another occasion) "has bestowed," as one sees, is bestowing, and probably will continue to bestow upon "Danish literature his special attention," says of Martensen's Dogmatik that one feels conviction in every line. Alas, I have now learned otherwise, that the only proof of a conviction is one's life. But are you quite sure, now, Mr. Wholesaler, do you dare say: By God. Think carefully now; you will see for yourself how important taking this oath could be, since this involves nothing less than—as Frederikke B. prophesies—the rebirth of theological scholarship in the North, and to which we add (what modesty no doubt has prevented Frederikke B. from adding) in North America. Do you dare, Mr. Wholesaler, do you dare say: By God. In view of the great importance of taking this oath, you yourself will perceive how important it is to do everything as solemnly as possible before proceeding to take the oath.28

***

Recollections from the Lives of the Pseudonyms: A Contribution to the Current Theological Controversy, by S.K.

Preface—The defense for the tone of this little essay is very briefly as follows. In his Dogmatiske Oplysninger Prof. Martensen bluntly declares that [my] pseudonyms are nothing but modes of expression. That does not bother me at all, for such conceit, in part stupid, warrants any tone whatsoever. The reader perhaps will not wonder at my finding it necessary to say this in advance before he has read what follows….

Introduction—Dogmatiske Oplysninger is published! Now this is what can be called clarification. If there is anything it does not clarify, then it must be because it does not appear in the book, and thus the clarification cannot be required to clarify it, at most one could ask that it be included in the clarification. It clarifies not only for us, but I am convinced that Fredrikke Bremer (who is linked by so many sympathetic bonds to Martensen's Dogmatik), as soon as she sees this light, will suspect, without any previous knowledge of it, that it is Martensen's clarification, unless she (who both read the book in advance in proof sheets, reviewed it in advance, declaring that M. would reform scholarship in the whole North, finally rushed off to N. America, presumably to prepare the way for the Dogmatik), unless she also knew in advance that Martensen had in mind the tactic, if attacks should come, of waiting until they were forgotten—and then to publish clarification....29

***

Prof. Martensen’s Status

It is now a good ten years since Prof. M. returned from his foreign travels, bringing with him the latest German philosophy and creating a great sensation with this new material―he who has really always been more of a reporter and a correspondent than an original thinker. It was the philosophy of standpoints―and this is what is corrupting in overviews of this sort―that enchanted the young people, opening the prospect of having everything ingested in half a year. He is hugely successful, and at the same time young students take the opportunity to inform the public in print that with Martensen a new era, epoch, epoch and era, etc. is beginning.…

….Then something new happens: Prof. M becomes a court preacher…He is again hugely successful at the Palace Church. He himself almost seems to be infatuated. He does not notice the many illusions: 1) the rumor that Hegelian philosophy had now come down to the cultured classes, to ladies, etc., who thought they had gotten some contact with it, a little taste of it, when he preached for them; 2) that [Bishop] Mynster was his protector; 3) that M. had not become a real priest, “not an ordinary man of the cloth for every Sunday,” but a court preacher for every 6th Sunday….30

Finally we return to scientific scholarship, and now the Christian Dogmatics is published….The earlier tradition of the speculative is exploited, while at the same time advancing the new opinion that―wonder of wonders!―it has now become so popular that every ordinary cultured person can read it and grasp it….In order that Christian Dogmatics does not lack for a forerunner, a lady novelist takes upon herself this honorable office: Miss Frederikke Bremer. She has—oh, God save us, she, too, is to be a judge!—with the consent of the author she has in advance accented herself with Christian Dogmatics. She announces in advance something that she of course can and will vouch for, both in advance and afterward: that this will be the rebirth of scholarship in Scandinavia. She implies that Martensen is Christ—and thereupon travels to North America, presumably to prepare him room and prepare the way.—As with the forerunner, so with all the rest of the entourage. [In the margin: absit risus ate scurrilitas! (now, no laughter and improper merriment!)]….31

Bremer is Martensen’s ‘profoundly prophesying’ prophet, his “forerunner” and “judge,” who “sees the light” and therefore Bremer “implies that Martensen is Christ” himself. On this last exaggeration Kierkegaard inverts the meaning of John 4:2-3 and Hebrews 6:20 to make a theological point: Fredrika Bremer is doing as she ought to in a profoundly misguided way by elevating Martensen as her prototype rather than placing that devotion directly in Christ.32 Though he never makes the connection himself, what Kierkegaard condemns of Martensen is reminiscent of Jesus calling the Pharisees whitewashed tombs in Matthew 23:27—he appears beautiful on the outside (being ’swathed in velvet’), but on the inside is full of uncleanliness and dead bones. That Martensen encourages Bremer as he does, flattering her with his attention because of her eagerness, is as bad as intentionally leading her astray for his own ego, according to Kierkegaard. In this Julia Watkin agrees, seeing in Martensen’s own recounting of Bremer’s visits that Martensen does not think highly of Bremer for her own sake: “Martinsen seems to have regarded Bremmer's interest in his Dogmatics as a useful test of the ability of his work to attract not only theologians and other scholars, but also ‘cultured members of the community.’ His tone towards her in his autobiography is decidedly condescending, not least about her attempts to work out her own theological position…”33 Whatever we think of Kierkegaard’s extreme dislike of Bremer, we have to see in it his even greater dislike of Martensen.

IV. Kierkegaard’s Accusation, and His View of Women

We can now return to Kierkegaard’s first accusation against Bremer, that not only did she have sex with multiple famous people, but that she also wanted to add Kierkegaard to her list. This is of course impossible to prove either way, but no other contemporary of Bremer’s voiced a similar accusation, including conservative personages who would have had no reservations in privately remarking on Bremer’s virtue should they have questioned her integrity. Indeed, almost all who knew Bremer spoke highly of her character.34 Bremer was not as radical as George Sand of France and her endorsement of “free love;” rather, Bremer’s desire in emancipation for women was to have a higher degree of economic and political independence, while still maintaining the values of the traditional family. Bremer thought much of the importance of good child-rearing and the moral roles both fathers and mothers modeled for their children. She also believed that women should be able to choose to marry, just as men might choose whether to marry or not, and that should a woman not wish to marry she might comfortably pursue her own interests through education and industry, just as a man might. This thinking, coupled with their own private decision making, is something Bremer and Kierkegaard share in common—an upholding of marriage as an important, virtuous institution, yet one that neither chose to enter into for the sake of their calling to be writers.35 Kierkegaard’s accusation of Bremer wishing to have sex with him, and her promiscuity with others such as Martensen (“who has had quite a lot to do with her”), says far more about Kierkegaard’s own view of propriety than any real observation of Bremer’s person (who, we must remember, Kierkegaard also never met personally).36

This brings us to the subject of Kierkegaard’s general view of women in society. The subject is complex, and beyond the scope of this essay to properly expound, but in short Kierkegaard holds men and women to be equal in every respect before God, yet considers this equality to be spiritual rather than temporal.37 Unlike some of his contemporaries, Kierkegaard does not believe women are inferior in their mental capacities. He does believe, though, that there are ontological differences between the male and female gender. In this respect, men and women balance each other out, while also modeling for the other areas that they ought to develop into. Men ought to be sensitive and pious as women are, while women ought to be discerning and thoughtful as men are. This view thus affects the subject of emancipation—since the spiritual ought to overcome and animate the temporal, men and women ought to be more concerned with accepting the placements and roles they find themselves in, serving one another in sacrificial love of neighbor. To be concerned with changing their station in life would be to misunderstand God’s revelation and power through suffering.38 Sylvia Walsh’s summation of Kierkegaard’s view of women is astute and helpful:

Coming into manhood at the beginning of the Victorian age, Kierkegaard shared the Victorian ideology of separate spheres for women and men. Nowhere is this more apparent in his authorship than in Part Two of Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, where he distinguishes between "woman's work," which consists in staying at home, keeping house, and being chiefly occupied with self-adornment, and "man's work," which involves going out into the world and earning a living. But this division of labor, even though based on what were believed to be natural differences between the sexes, does not appear to be rigid in his thought inasmuch as he recognized legitimate public professions for women, such as writing and acting. Like American fundamentalists, however, Kierkegaard and his pseudonyms consistently opposed the emancipation of women, regarding it variously as a male plot to corrupt and exploit women and as "an invention of the devil.” Although Kierkegaard just as consistently affirmed the spiritual equality of man and woman, in his view that is not equivalent to social equality or equal rights, nor is the latter something Christianity has "required or desired" to establish in the temporal realm. Rather, "[t]he man is to be the woman's master and she subservient to him.”39

Julia Watkin also practically notes that Kierkegaard did not grow up in a household of educated women, with all three older sisters expected to do household work that servants normally did for families of the Kierkegaards’ station.40 Kierkegaard’s own mother was illiterate, and all of the women of Kierkegaard’s family had died by the time he was twenty-one.41 Kierkegaard did, however, support his niece Anna Henriette Lund’s education at school, rather than see her receive home tutoring.42

There is a particular snag, however, found in Kierkegaard’s journals, that problematizes a critique of Kierkegaard’s view of women’s emancipation. Sylvia Walsh, Julia Watkin, and M.G. Piety all highlight it in their own writings, that Kierkegaard found modern society destructive to men, who were expected to integrate into it in order to survive.

There really is something to the view that one ultimately finds a bit more self-sacrifice among women, which is no doubt because they live quieter and more withdrawn lives and thus a little closer to ideality; they don’t as easily acquire the market-place measures used by men, who get right to the business of life. What saves women is the distance from life that is granted them for so long (which is why even among women one sometimes sees traces of and expressions of individuality, the boldness to grasp a single idea and hold on to it). This quieter life means that women are sometimes more loyal to themselves than men are, since men are demoralized from boyhood by the demand to be like the others, and become completely demoralized as youths, not to mention as men, by being taught all about the way things are in practical life, in reality. It is this very competence that is ruinous. If girls are brought up in the same way, one can say goodnight to the whole human race. And women’s emancipation, which tends toward this very sort of education, is no doubt the invention of the devil.43

The logic is easy to follow, if this estimation is true—why apply oneself to support the cause of bringing women into modern life when as a system it is detrimental to one’s individuality? For Kierkegaard the thought appears to conclude that men simply have to accept this “ruinous” suffering for themselves, just as women have to accept whatever inconveniences come from their reliance upon men. It perhaps was too idealistic to contend that change to the structures of “practical life in reality” itself needed to happen, for the sake of men and women alike. Kierkegaard’s answer to the issue of a subjugated, “demoralized” soul was not to try and change society’s structures, but to instead emphasize the deeper reality of one’s spiritual equality with one another before God. By emphasizing one’s need of the other in the present, and becoming willfully dependent upon God while waiting for Christ to ‘draw all things unto himself,’ a good life could be imagined. Men and women’s need of each other, and giftings to that effect, were to be showcased in how modern society was found to be, rather than in how society ought to be.

Though Kierkegaard correctly saw how many aspects to the structure of modern society inherently alienates a person from his or herself, and also from one another in a struggle to out-perform one another, it is nevertheless a shame he did not also see that offering women license in the world might change the world for the better, rather than merely suck women into the pre-existing problems of modernity.

V. Bremer on Kierkegaard Again: Hertha

Kierkegaard did not live to see Bremer’s seminal novel Hertha come out in 1856, where Bremer once again engaged with Kierkegaard’s thought via his attack essay “This Must Be Said, So Let it Be Said.” Bremer considered Hertha to be her literary masterpiece, having took a calculated risk by writing a novel that openly, dramatically discussed the need for women to self-determine their lives.44 Kierkegaard appears midway through Hertha, while the protagonist Hertha Falk is traveling in her native Sweden. A friendly stranger “with a polite and kind expression” sees that Hertha is morose, so he goes below the deck of their steamboat in order to retrieve a pamphlet for her:

[S]he sat with her eyes riveted upon the tract which she held in her hand. By degrees some words attracted her eye, and she read as follows, in Danish:

‘To be agonized as I am, and still may be, is certainly what no one, humanly speaking, can call desirable; nevertheless, it may be that which, in a much higher state, I may thank God for as the greatest benefit. To be agonized and brought low, even for a noble cause, is, I can very well understand, something which one, humanly speaking, cannot desire, something which one would wish to avoid at almost any price, if, by experience, one were not exalted by the thought, that in a far higher point of view, this extreme of suffering may be regarded as the greatest benefit.’

Hertha turned the page and continued to read:

‘April 11: In torments which a human being has seldom survived; in agonies of mind of eight days’ endurance, which were enough to deprive the mind of reason, I am yet sufficiently ——

‘My wishes have often been for death, my longings for the grave! my desire that my wishes and my longings might be fulfilled. Yes, O God! if thou wert not Almighty; if thou couldst not all-powerfully compel; if thou wert not love which could move irresistibly; on no other condition, at no other price could I be induced to choose the life which is mine, again to be embittered by its unavoidable consequences, the effect which mankind produces upon me.

‘Yet thy love, O God! prompts the thought of daring to love thee, inspires me under the possibility of being all-powerfully compelled—joyfully and gratefully to desire to become that which is the consequence of being loved by thee and of loving thee; a sacrifice offered for a race to whom the ideal is a foolishness, a nothing, to whom the earthly, the temporal, are the only real.’

Hertha did not inquire by whom this heart-rending confession was made [asterisked below: “S. Kierkegaard, in his last “Moment”]; but she felt that a combating and suffering heart throbbed here in unison with her own, embittered, bleeding, loving, and still, though as in the midst of the flames, seeking to lay hold upon God; and she felt less solitary in the world.45

Hertha decides to allow the company she is with to continue on their river cruise without her, while she stays behind to think in solitude.

When the steamer burst forward through the locks of Trollhätta on its way into the beautiful river, Hertha was sitting along on Gull, or Gold Island, with the thundering falls roaring around her, and the words of Kierkegaard in her hand. The deafening thunder of the fall seemed to her a lullaby which would hush to sleep the wild combat in her breast, and for the moment it did so. When evening came, and with it darkness, she went to the Inn, and ordered and obtained for herself a room.

She passed a sleepless night. With the first flush of dawn she went out…[and she recommenced] her wandering immediately, from the necessity of allaying the torture of the soul by the weakness of the body, and to gain a moment’s forgetfulness of life and suffering—a moment’s sleep. But all the more seemed darkness and the horrors of darkness to encompass her soul. Energetic natures are able to suffer a great deal without being crushed or subdued; nevertheless, there is a state in which they have great difficulty in sustaining themselves….Suffering, in its extremest form, causes to us the loss of our higher consciousness, our light and our strength. If any one had asked the restless wanderer by the fall of Trollhätta, at this time, what she was seeking for, she might have replied—“Myself!”

The words of Kierkegaard no longer consoled her. The spirit which spoke to her in them was too much absorbed by the combat, had not yet passed victoriously through it. In the dark tumultuous state of mind in which she then was, she threw the printed tract into the foaming waters. It whirled round for a moment, sank, and vanished from sight. How beautiful to sink thus, to vanish in the cool depths, and forget, and rest;—the thundering, whirling waters would be heard there no longer!46

It is interesting that Bremer did not wholly write Kierkegaard off after his refusal to meet with her in 1849. It seems out of a sense of fascination, hope, and then genuine disappointment that Bremer continues to track along with Kierkegaard’s output and incorporate his thought into her novel on women’s emancipation. She may not have read Stages on Life’s Way, but it seems she did read some or all of Kierkegaard’s magazine articles under the title “The Moment,” which first saw publication in 1854. This could perhaps be seen as a recognition of respect, followed by a scolding for still missing the picture after understanding so much. Kierkegaard saw in his time a critical moment, yet either wouldn’t or couldn’t recognize the frustrations of women in that moment.47 For Bremer, this is failure and oversight.48

VI. Concluding Thoughts

While researching and writing this piece, the idiom “like ships passing in the night” kept coming to mind. In judgement of Kierkegaard and of Bremer I find fault with both of them, much sympathy with each, and something like a heaviness of heart that all too often in our encounters with each other we do not see or understand one another. Both had important missions to accomplish: Bremer’s was to bring lasting change into the lives of women, Kierkegaard’s was to foster in others a submissive life of friendship with the living Jesus Christ. This is a similarity shared between them, too: both had messages they wished would bring a change for the better upon the lives of the individuals making up their societies, and both were frustrated by a lack of recognition and understanding from their wider societies (Bremer at least being so through Hertha).

Taking everything together, Kierkegaard’s dislike of Bremer is almost exclusively owing to her great admiration of Martensen. It has less to do with her gender, and more to do with her impressionable embrace of Martensen’s philosophy, of which her published endorsement served to uphold and further Martensen’s public image while simultaneously damaging Kierkegaard’s. One gets the sense from Kierkegaard’s manner of expression that Bremer’s gender does subtly come into why she is impressionable, but that would be more owing to her lacking university-honed skills rather than it being something fundamental to her being a woman. Bremer’s friendliness with Martensen is even a likely reason why Kierkegaard did not wish to meet with her—Copenhagen being a small city at the time, Kierkegaard indicates in his journal that he had known of Bremer’s presence in Copenhagen, and it is notable that Bremer only asked to meet with Kierkegaard after months of already having been in Copenhagen. With her note indicating only a loose familiarity with Stages on Life’s Way, Kierkegaard was not unreasonable to suspect that Bremer was approaching him with pre-esetablished opinion and motive. Kierkegaard did not like people who wished to enfold him into their personal intellectual agendas, whichever gender they might be. Some would call this ego, others would allow it as the rare trait of radical conformity to one’s own views. Perhaps it is both.

Where Kierkegaard’s personal view of women seem to most clearly to bear upon his views of Bremer are his accusations of her sexual promiscuity. One can detect a chiding in his draft refusal to Bremer’s request for a visit, indicating a suspicion that she is flirting with him. Outside readers can largely agree that Bremer was not intending to flirt with or alarm Kierkegaard, but one can also see how Kierkegaard could misunderstand her, when he held an ulterior respect for women who are more modest in their manners and addresses. Bremer’s actions and still-developing reputation as a suffragette possibly played a role in Kierkegaard’s decision not to call on her, but if it did it was far from being the sole or primary reason.

In the end, both Bremer and Kierkegaard at least are unified by this—that the only proof of a conviction is how one lives one’s life.

Bibliography and Suggested Further Reading

Primary Sources

1. “Does a Human Being Have the Right to Let Himself Be Put to Death for the Truth?” in Two Ethical-Religious Essays in Without Authority, Princeton, 1997.

2. Kierkegaard’s Letters and Documents, Princeton University Press, 1979.

3. Kierkegaard’s Journals and Notebooks, Princeton University Press, 2007-2020.

4. Søren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Papers, Indianna University Press, 1967-1978.

5. The Corsair Affair and Articles Related to the Writings, Princeton University Press, 1982.

6. The Concept of Irony: With Continual Reference to Socrates, Princeton University Press, 1990.

7. The Moment and Other Late Writings, Princeton University Press, 1998.

8. An Easter Offering, Fredrika Bremer (trans. Mary Howit), 1850.

9. Hertha, Fredrika Bremer (trans. Mary Howit), 1856.

10. Christian Dogmatics, Hans Lassen Martensen (trans. Rev. William Urwick), 1874.

11. Christian Ethics, Hans Lassen Martensen (trans. C. Spence), 1882.

Secondary Sources

1. “H. L. Martensen” by Bruce Kirmmse in Kierkegaard in Golden Age Denmark, Indiana University Press, 1990.

2. Hans Lassen Martensen: Theologian, Philosopher, and Social Critic, edited by Jon Stewart, University of Chicago Press, 2012.

3. “Hans Lassen Martensen: A Speculative Theologian Determining the Agenda of the Day“ in Kierkegaard and His Danish Contemporaries, Tome II: Theology, Ashgate Publishing, 2009.

4. Kierkegaard: A Biography, Alistair Hannay, Cambridge University Press, 2001.

5. Kierkegaard on Woman, Gender, and Love, Sylvia Walsh, Mercer University Press, 2022.

6. “Mathilde Fibiger: Kierkegaard and the Emancipation of Women” by Katalin Nunn in Kierkegaard and His Danish Contemporaries: Tome III, Literature, Drama, and Aesthetics, Ashgate Publishing, 2009.

7. “Rasmus Nielsen: From the Object of ‘Prodigious Concern’ to a ‘Windbag’” in Kierkegaard and His Danish Contemporaries Tome I: Philosophy, Politics, and Social Theory, Ashgate Publishing, 2009.

8. “’Serious Jest?’ Kierkegaard as Young Polemicist in ‘Defense’ of Women,” by Julia Watkin in The International Kierkegaard Commentary: Early Polemical Writings, edited by Robert Perkins, Mercer University Press, 1999.

9. “The 'Emancipated Ladies' of America in the Travel Writing of Fredrika Bremer and Alexandra Gripenberg,” Sirpa Salenius, Journal of International Women's Studies Vol. 14 Is. 1, 2013.

10. “Victoria Benedictsson: A Female Perspective on Ethics,” Camilla Brudin Borg in Volume 12, Tome III: Kierkegaard's Influence on Literature, Criticism and Art Sweden and Norway, Routledge, 2013.

Online Resources:

Søren Kierkegaard and the Corsair Affair: Public Shaming and the Assertion of the Individual

Proof of Kierkegaard in 19th Century America

Fredrika Bremer

Kierkegaard on Women

The Myth of Kierkegaard’s Misogyny

Footnotes:

Letter no. 201, Kierkegaard’s Letters and Documents (Princeton, 1979).

Letter no. 203, Kierkegaard’s Letters and Documents.

Letter no. 204, Kierkegaard’s Letters and Documents.

Other pseudonyms present in the first part of Stages on Life’s Way are Constantin Constantius of the book Repetition, Johannes the Seducer of Either/Or, and a new character by the name of William Afham. It has been noted by Georg Brandes and others that with “In Vino Veritas” Kierkegaard was riffing off of Plato’s Symposium in both design and subject matter.

The best detailing of “the Corsair affair” remains the Hongs’ introduction to their Princeton University Press volume of the primary material. A free, online resource that also gives an overview is “Søren Kierkegaard and the Corsair Affair: Public Shaming and the Assertion of the Individual,” linked to this essay under “Online Resources.”

And appearing in English almost immediately after—see my post Proof of Kierkegaard in 19th century America for more on this.

p. 115, “The 'Emancipated Ladies' of America in the Travel Writing of Fredrika Bremer and Alexandra Gripenberg,” Sirpa Salenius, Journal of International Women's Studies Vol. 14 Is. 1, 2013.

In this way Johan Ludvig Heiberg and Hans Lassen Martensen enjoy the special privilege of being mentioned more than once in her book—Heiberg in relation to the theater and the “literati” of the city, Martensen as first a preacher “whom no one can hear without admiration and delight,” and then as an esteemed philosopher.

p. 23, An Easter Offering (1850).

p. 22, An Easter Offering.

Bremer writes: “God’s will be done, I say, along with S. Kierkegaard. Would that we might have a sense of assurance that we are following His exhortation and carrying out His commandment to us! With respect to your Danish Simmon Stylites, he has awakened a great deal of interest, even here [in Sweden]. Most people – myself included – know that he was right in much and wrong in much. He is no pure manifestation of the truth, and his sickly bitterness has certainly stood in the way of clarity and reasonableness in the judgments reached about him.” Breve til Hans Christian Andersen, 674; see p. 81 in The International Kierkegaard Commentary: Early Polemical Writings.

Simon Stylites is reference to Saint Simeon Stylities (390-459), who was a Syrian Christian hermit famous for beginning the movement of ‘pillar hermits’, where an individual would enclose himself atop a column or pillar and dedicate himself to prayer, being entirely dependent upon others to care for his needs.

See pp. 112-116, 133, 135 in The Corsair Affair.

If space allowed, it would be interesting to further consider Bremer’s own layered view of women, and the distinctions she makes between gender and gender roles. One gets the sense that Bremer does not include herself with the ladies who are “principally” interested in a philosophy of the heart. “Ladies” might be interested, but Bremer stands outside and above such a narrow fixation.

These entries, note, are not to be found in a single publication of Kierkegaard’s journals into English. The complete list of Kierkegaard’s mention of Fredrika Bremer in his journals, determined to the best of my ability, are: (1) Pap X1 A 658 // NB12:115, (2) Pap X2 A 25 // JP 6493 // NB12:157, (3) Pap X2 A 155 // NB13:86, (4) Pap X3 A 105 // NB18:58, (5) Pap X6 B 105 // JP 6475, (6) Pap X6 B 137 // JP 6636.

For some brief background — English readers of Kierkegaard have two “complete” editions from which to consult his private journals and loose papers: Søren Kierkegaard’s Journals and Papers (“JP”, Indianna University Press, 1967-1978), and Kierkegaard’s Journals and Notebooks (“KJN”, Princeton University Press, 2007-2020). While both purport to be complete editions, they do sometimes contain omissions, which means amateur and professional scholars alike need to carefully examine both editions, along with the Danish Søren Kierkegaard’s Skrifter via dictionary aid and key word searching, in order to find what they are looking for. Unfortunately you cannot trust the indexes provided by JP or SKS/KJN to be accurate or exhaustive, and you must also note that there are occasional discrepancies between the online and physical editions of these resources. The older Danish editions of Kierkegaard’s complete journals and papers, called by the shorthand “Papier” or “Pap,” are your friend, serving as the only common link between JP, SKS, and KJN.

In the case of Kierkegaard’s thoughts on Fredrika Bremer, the JP lists 5 entries in their index, two of which are errors: JP 6916 does not mention Bremer, and JP 1:707 is only an excerpt of the larger journal entry…strangely, while it correctly includes Pap X1 A 658 as containing mention of Bremer, the Hongs’ translation of the section of the entry is a part that does not speak about Bremer. Overall, then, the JP correctly identifies and translates 3 of the 6 mentions of Bremer in Kierkegaard’s journals, 2 of which are not available to be read in either the SKS or the KJN. This omission is reflected in the SKS cross reference sheet—the Bremer entries Pap X6 B 105 and Pap X6 B 137 are missing from the list, but we know that they exist because of the JP’s translation of them.

NB12:115 / Pap X1 A 658. “R. Nielsen” refers to the philosopher Rasmus Nielsen (1809-1884), who was an important figure of his day. Kierkegaard and Nielsen respected each other’s work, if often disagreeing with one another, and for a time were friends. Nielsen was professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Copenhagen beginning in 1841, and published in multiple fields of philosophy throughout his long career. Nielsen ended up being a defender of Kierkegaard after his death, including an 1858 article where he tries to show that Kierkegaard was not jealous of Bishop Mynster or inconsistent with his original purposes of bringing existential awakening to the church in Kierkegaard’s final, open attack on the Danish Church. (see “Rasmus Nielsen: From the Object of ‘Prodigious Concern’ to a ‘Windbag’” in Kierkegaard and His Danish Contemporaries Tome I: Philosophy, Politics, and Social Theory (2009)).

Good resources on Han Lassen Martensen are the chapter “H. L. Martensen” in Bruce Kirmmse’s Kierkegaard in Golden Age Denmark (1990; available to borrow on Internet Archive); also “Hans Lassen Martensen: A Speculative Theologian Determining the Agenda of the Day“ in Kierkegaard and His Danish Contemporaries, Tome II: Theology (2009), and Hans Lassen Martensen: Theologian, Philosopher, and Social Critic edited by Jon Stewart (2012; partially available on Google Books). An extended cross-analysis between Martensen’s and Kierkegaard’s personal relationship over the course of the latter’s life remains difficult to find in one place, in English. Nevertheless, a general awareness of who Martensen was is critical for understanding Kierkegaard’s own theology, as in Martensen Kierkegaard saw represented much of what was wrong with his day and age.

p. 51, Kierkegaard: A Biography by Alistair Hannay.

p. 222, “Kierkegaard’s Enigmatic Reference to Martensen in The Concept of Irony” by Jon Stewart in Hans Lassen Martensen: Theologian, Philosopher, and Social Critic (2012).

See p. xi-xii in the historical introduction to Princeton’s translation of The Concept of Irony: With Continual Reference to Socrates.

See p. 219-228, 230-236, 302-305 of Christian Ethics by Hans Lassen Martensen, available for viewing on HathiTrust.

Namely, with humility and contrition.

For those familiar with Barth and Brunner’s controversy, the analogy might help. Brunner wanted to see Barth as landing within his conception of the intersection of divine and human agency; Martensen wanted to see Kierkegaard’s stubborn ‘one-sidedness’ land within his own mediation of Jesus Christ as complete and total human truth.

p. 22, An Easter Offering.

JP 6493 / NB12:157 / Pap X2 A 25. JP translation is provided, with some slight changes from the KJN for readability.

See NB12:76 and p. 396 in Christian Dogmatics (English trans 1874).

NB18:58 / Pap X3 A 105.

See NB12:110 — “Mob vulgarity had triumphed in Copenhagen, to a certain extent in Denmark. Everyone, those who ought to provide standards of judgment, the journalists, even the police, despaired and said, There is nothing to be done here. And of course the mob vulgarity increased and triumphed…They all remained silent. Here came the treachery―at that moment I saw that my position with respect to the bourgeoisie was gradually being eroded and would for the most part be irretrievably lost. Wretched age! The possibility I had otherwise reserved for myself―to live pleasantly in the country when I retire from being an author, owing to my literary reputation ranked not a little above the modest position of a country priest―has been lost. When a person has been marked like this it is a burden to live in the countryside.”

JP 6475 / Pap X6 B 105. Mendel Levin Nathanson (1780-1868) was editor of Denmark's oldest and largest newspaper, Berlingske Tidende, as well as a merchant and writer on finance and trade.

JP 6636 / Pap X6 B 137; shortened.

Bruce Kirmmse offers some clarification on what Kierkegaard is referring to when he says that Bishop Jacob Peter Mynster (1775-1854) was Martensen’s protector, and that Martensen’s promotion to a court preacher is not the same as being a real priest — “[By the early 1840s] Martensen became the principal recipient of Mynster's patronage, and it was with Mynster's assistance that Martensen was promoted to professor in 1840 and elected to the Royal Scientific Society soon after. Martensen relates in his memoirs that in the course of the 1840's Mynster "came to the view that I ought to unite a position in the Church with my University position, and he caused me to be named as Court Preacher in 1845." [Court Preacher was responsible for preaching to the king and queen of Denmark]. "Mynster never said to me that I should be his successor. (That would of course have been very gauche.) But he did indeed say that if I should ever desire an episcopal post in the future, it was important that the preaching of the Word not be foreign to me." Mynster thus sponsored Martensen's elevation to the high ecclesiastical post, and three years later helped secure Martensen's election as a Knight of the Dannebrog, the highest order of the kingdom. In the 1840's Martensen became a regular member of Mynster's inner circle, and, having received all this favor, it is not surprising that Martensen cites Mynster again and again in his Christian Dogmatics (1849) as an important authority in a number of weighty theological matters. Yet, in spite of all this grooming and protection, which was quite apparent to other observers, Martensen insists that he never “desired” the post of Bishop of Zealand nor “suspected” at the time that he was being prepared for it.” p. 187-188, Kirmmse, Kierkegaard in Golden-Age Denmark.

NB13:86 / Pap X2 A 155; shortened.

Christ as prototype is a concept Kierkegaard especially highlights in his Practice in Christianity, which was written and published in the immediate aftermath of Bremer’s Copenhagen visit.

p. 16n36, “‘Serious Jest?’ Kierkegaard as Young Polemicist in ‘Defense" of Women’” by Julia Watkin in International Kierkegaard Commentary: Early Polemical Writings (1999). The entry in Martensen’s biography reads as follows: “As it happened, the first person who read my Dogmatics bit by bit in proofs, was a lady, the poet Frederike Bremer, author of the Swedish ‘Stories of Everyday Life.’ That year she was staying in Copenhagen and frequently came to my house, speaking with me a great deal about religious matters and wanting to learn about dogmatics....I recall with joy the many evening hours that she came to my room and spoke of what had moved and edified her in the work―she thought that I had constructed the intellectual equivalent of a cathedral―but she also set forth her doubts and misgivings. Even though she has a religious temperament and a Christian tendency, like so many cultivated people, she was ensnared in a one-sided humanism and had difficulties in acquiring a consciousness of sin and guilt....Therefore we had to have a number of conversations about sin and grace. And she always interested me as a member of the congregation who attempted to absorb my presentation of the doctrines of the faith.” (p. 550, notes to Journal NB12).

We have, for example, the Amerian poet James Russell Lowell’s recollection of Bremer: “I do not like her, I love her. She is one of the most beautiful persons I have ever known—so clear, so simple, so right-minded and -hearted, and so full of judgement.” pp. 1–10, “Fredrika Bremer’s Unpublished Letters to the Downings,” Scandinavian Studies and Notes 11, No. 1 (1930); p. 137.

Kierkegaard famously broke off his engagement with Regine Olson, despite the love on both sides, and Bremer refused a proposal of marriage from her life-long friend Per Johan Böklin, citing her call to be a writer as more important than her regard for him; see Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon’s article on Fredrika Bremer.

Scholars have dismissed Kierkegaard’s accusation as unfounded too, though in part because of a disagreement on the meaning “legemlig Omgang.” Watkin calls the phrase “legemlig Omgang” ambiguous (see p.13n8 “‘Serious Jest?’”), faulting Rosenmeier for translating it to “sexual intercourse” in Kierkegaard’s Letters and Documents (see p. 483 LD), but the KJN editors clarify that though “legemlig Omgang” literally means “confidential social contact,” Kierkegaard means to insinuate sex because of his following claim “but I was virtuous.” They thereby render “physical intercourse” in their translation of NB12:115 / Pap X1 A 658.

For shorter, accessible pieces on Kierkegaard’s view of women, Kierkegaard scholar M.G. Piety has written a few blog posts: Kierkegaard on Women, and The Myth of Kierkegaard’s Misogyny.

Kierkegaard’s essay “Does a Human Being Have the Right to Let Himself Be Put to Death for the Truth?” (written under the pseudonym H.H.) should be considered on this matter alongside the other usual places one reads of this theology in Works of Love, Sickness Unto Death, Christian Discourses, and Practice in Christianity. This essay can be located in Two Ethical-Religious Essays published in Without Authority (Princeton, 1997).

p. 251-252, Kierkegaard on Woman, Gender, and Love. In-text references have been removed for the sake of readability.

p. 10, “‘Serious Jest?’”

Kierkegaard had three older sisters, Maren Kirstine, Nicoline Christine, and Petrea Severine, who all died between 1822-1834. Kierkegaard’s mother, Ane Sørensdatter Lund Kierkegaard, died 25 days before Petrea Severine did in 1834.

p. 10, “‘Serious Jest?’”

NB11:159.

The risk paid off when the Swedish parliament passed a reform on unmarried women’s rights between 1858-1863.

p. 241-243, Hertha (1856). See p. 75, 78 in The Moment and Later Writings (Princeton, 1998) for Bremer’s extracts of Kierkegaard in context.

p. 244-245, Hertha.

Katalin Nunn is fascinated that Kierkegaard seems to purposefully avoid any serious engagement on the subject of emancipation, when it was such a discussed topic of the day. Speaking of Kierkegaard’s unpublished review of Mathilde Fibiger’s emancipation novel, the first of its kind in Denmark, she notes: “Kierkegaard, for some unknown reason, avoided treating the novel [Clara Raphael]’s central issue: that is, whether and how the status and rights of women could be improved in society. This is surprising given the fact that Kierkegaard wrote about related topics frequently in some of his other works and was well familiar with the problem. Nevertheless, he did not use the opportunity to write about this issue, when it was at the center of the interest of many of his contemporaries.” p. 84-85, “Mathilde Fibiger: Kierkegaard and the Emancipation of Women” in Kierkegaard and His Danish Contemporaries: Tome III, Literature, Drama, and Aesthetics (2009).

It should be noted somewhere that not all women were for emancipation, such as the Danish authoress Thomasine Gyllembourg.

Katherine - Wonderful!!! I really enjoyed following this important story of "two ships passing in the night" - how true, and yet given the circumstances, could it have been otherwise at the time?